Learn from me – if not by my precepts, at least by my example – how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge, and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, than he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.

Victor Frankenstein, “Frankenstein” by Mary Shelley. 1818.

Consider the potential we as a species have when we apply information and create knowledge. That said, knowledge in itself is not inherently dangerous, yet its application on the physical and mental have a knock-on effect that, for lack of an aphorism, is catastrophic or uplifting. The same realization Oppenheimer had at his once noble pursuit resulted in lives lost, stood as a literary classic from Odin to Gilgamesh, where knowledge is a burden one would be best left without. This post is a small discussion on the connections and reflections in Mary Shelley’s Victorian science-fiction novel Frankenstein (the 1818 text) and Christopher Marlowe’s Elizabethan play, “Doctor Faustus”. Specifically, on their handling of power and the ethics behind them: because you can, should you? First, this is born from an ambition to create or modify existing life, and “ambition” is interpreted two ways in fiction.

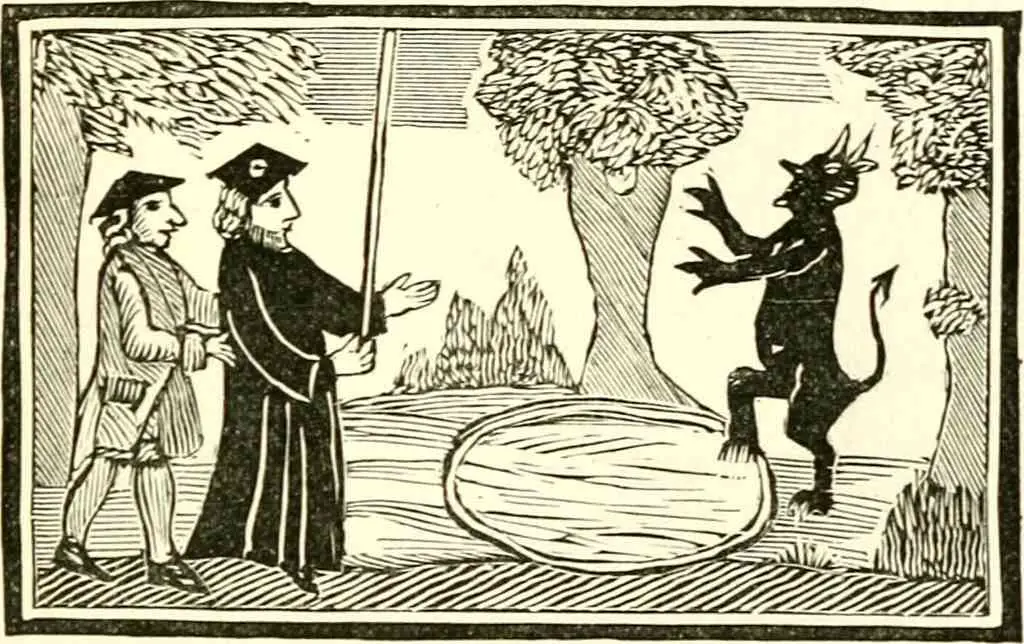

First, ambition is considered our greatest trait, it compels us to make satisfying progress toward a concrete goal and sets a boundary for our potential as a human. However, one of the earlier known examples of ambition in the hands of the unsteady is seen in Doctor Faustus (B text). Faustus, having achieved mastery over the sciences, the law, and lifesaving practices, has turned to necromancy (which is quite similar to Frankenstein’s own behaviors) and the play portrays this as a volatile behavior that can be twisted into a malignant force.

In line with Elizabethan oxymoronic wordplay, Duality as a writing mechanic comes into play with Marlowe. Hope vs fear, salvation vs damnation, heaven vs hell, free-will vs control, seeking vs desiring, beauty vs atrocity, knowledge vs ignorance, these binary forms demonstrate an eerie lack of impact in meaning without context. The simple black vs white vs grey triumvirate holds an infinite spectrum characters often find themselves caught in when confronting manners of power and morality.

As things come in threes, consider the three sides, levels, or ideas to ambition shown in the play:

One: delusions of grandeur leading man to assume his ambition serves a greater purpose. Example: power to command all life could result in preserving health and ensuring eternal life for all on earth. In Act I, Faustus swears that his command of necromancy would allow him to change the world in service of mankind, despite his theological questioning of the art. In this stage, he presumes that he will unlock the celestial mysteries of the world and remain untainted by virtue of his accrued skills and knowledge of a lifetime of study. His recollection of Icarus is not unnoticed, as he believes he can avoid this fate with foreknowledge.

Two: Faustus has acquired the dark power… to play tricks upon the population. Where he could raise and command armies, he opts to fly and annoy others.

Where his eyes could now “open”, he finds he still cannot describe Heaven nor Hell in words, and his newfound powers cause Lucifer himself to appear to offer honest terms of engagement, allowing Faustus to relinquish his powers if he wishes. His assertive statement, dripping with confidence that he could become the emperor of the world gains Lucifer’s attention; his new goal is not to save the world, but to be superior to mankind. Yet it is his murder of Benvolio that serves as the catalyst for his descent into Hell.

Three: Faustus begins to reflect on his actions and coming fate by midnight. Through great emotional and spiritual turmoil, he begins to accept his fate. That is until he can visually see God’s judgment. A final opportunity to rise to the surface and gain the light, imagining his Helen, only to end his life in fear. Nowhere is safe. God’s punishment is too much to bear, the Earth despises him, and Hell awaits him for torment.

The magnitude of power resulting from Faustus’ pursuit of knowledge gives a solemn recollection of Hell from Mephistopheles’ perspective:

Why is this hell, nor am I out of it.

Doctor Faustus, Act III lines 76-86.

Think’st thou that I, who saw the face of God,

And tasted the eternal joys of heaven,

Am not tormented with ten thousand hells

In being deprived of everlasting bliss?

O Faustus, leave these frivolous demands,

Which strike a terror to my fainting soul.

FAUSTUS: What, is great Mephastophilis so passionate

For being deprivèd of the joys of heaven?

Learn thou of Faustus manly fortitude,

And scorn those joys thou never shalt possess.

Faustus demonstrates willing blindness to his behaviors, understanding that his soul is at risk and still seeking power to dominate the world. A demon himself, Mephistopheles attempts to guide Faustus back to the living path and against the Hell that Mephistopheles fears.

The parallel of character development becomes more apparent as the play progresses; Faustus slowly descends into pride and greed, forsaking his God among other sins that seal his fate, while Mephistopheles seeks not redemption, but for Faustus’ realization of his err. Like Faustus, he has pursued the dangerous, rebelled, and was damned for his sins. The firsthand account of a demon to counter Faustus’ excitable dismissal of Hell beckons as painful reality, and this knowledge urges him to guide Faustus in a way unbecoming of demons – in the modern sense.

We are shown that Faustus hears and reads the words, but does not understand the meanings, given his Renaissance Man qualities, this is not surprising. Affirmation, discovery and creation of knowledge is the forethought of natural scientists, yet Faustus enjoys the power in his hands until his panicked descent into hell.

To Tame Our Native Psyche

A central theme in Frankenstein has knowledge as a core idea; the element of knowledge must be tamed and tempered with the multi-dimensional mind map of an aspiring contributor to humanity’s growing stores of infinite knowledge. What is frightening is exactly what we consider a knowing, as shucking corn to outer space encompasses this ever-expanding concept. Shelley’s novel is concerned with the connection between knowledge and quality of life. A sentiment that drove Frankenstein to madness and regret, there are dire consequences for the cast of the novel who are victimized by their apprehension of the arcane, the forbidden. That which should remain a question for all time. Alas, our ambition precedes us. We cannot help but ask questions of the world that its inhabitants could not teach us.

In Victor’s relentless inquiry into the creation of life, which is not detailed so as to inspire 19th century readers, is at first a reflection of Shelley’s own personal misfortune between miscarriage and the loss of her husband, and is second a broader question: should man control the finances and flow of information in the world, what if man alone could host life. Which itself is a critique of natural philosophy – the original name of what would evolve into British chemistry – and its relation to obsession with the unknown. Would man control a new life as he does business, relationships, human rights? If we consider how politics behaves today, in 2023, Shelley makes a poignant observation.

Dr. Frankenstein demonstrates a great command of knowledge no doubt inspired by his mentors at the University of Ingolstadt, and in youth seeks the elixir of life, immortality specifically, after his mother’s untimely death from scarlet fever. With heavy research in alchemy, the occult and galvanism, he experiments with mundane forces of nature: electricity, gunpowder, and magnetism to spark life in a compiled body of cadavers. To his horror the monstrosity he has created is quickly shunned and sent away from civilization. All from Victor’s obsession with the simpler, plaguing questions of mankind:

Where do we go when we die? Where does all life come from? If one man can conquer death, how would the world inherit goodness, knowing their lives could be infinite? Is seeking knowledge relentlessly and selflessly to hone a better future a flaw? Victor’s obsession and eventual success at creating life is considered a virtue by Shelley’s storytelling. In the direct opposite, one who brings death (as the creature has) must indicate a flaw. His first and prime opportunity to teach his creature the modicum of moral excellence is defiled by emotional exigency. Interestingly, Clerval’s voyage to accompany Victor opposes his story, which sees him abandon and fear his creation.

The creature’s poignant statement on morality holds weight:

To be a great and virtuous man appeared the highest honour that can befall a sensitive being; to be base and vicious, as many on record have been, appeared the lowest degradation, a condition more abject than that of the blind mole or harmless worm” (p 100).

Frankenstein; or; the Modern Prometheus, the 1818 Text. p100

Indeed, knowledge, and ambition born before and after gaining this knowledge is perceived negatively. This is especially true for the creature, whose sorrow has increased along with his encyclopedic knowledge gain. He even argues that alleviating himself from thought, contemplation and constant paranoia would bring him happiness, figuring that if not a partner, then only death could satiate his mind and heart. A heavy burden for a two year old creation.

To make matters more complicated, the concept of creation surpasses the physical form of the creature, dipping into metaphor at times following Volume II through Gothic metaphysics. Knowledge is inherently connected to the Gothic mode of thought, as it concerns itself with a character’s state of mind, reasoning and assesses the readers’ ability to either take the supernatural or temporal illusion of the five senses. To know is to be aware of oneself. Epistemological texts also form the core of Gothic studies through fear. Characters in these texts quickly identify their skill in analyzing reality through their current struggles and dangers. In Frankenstein, knowledge and creation are pairs and means of causation, giving Victor more than fear. He embodies dread toward himself and his creations, leading to the deaths of his brother and innocent neighbor.

Victor’s attempt to create life without consideration of consequences is, while representative of rogue and potentially effective science, morally unjust. An example for his creation; while Victor’s attempts violate the natural order of the world to play God, the irony lies in his inability to fulfill his role as an arbiter of life. He understands the weight before him, but cannot identify his character flaw. Ambition in fiction is considered a tragic virtue, than a tragic flaw.

Who We Are in the Dark

The question can become, should one pursue dangerous knowledge if it means violating every moral and ethical value set in place by international standards? When done in complete secrecy, these are ignored. I am reminded of a line in Heavenly Delusion, where the Director questions if her implanting her brain into a younger, non-consenting body is considered illegal, immoral or sacrilegious when it happens somewhere untouched by the public, where the world knows not of its existence. For reference, this location in the manga hosts human/animal experimental test subjects for the sake of developing unnatural powers for her to take over.

One might argue that science cannot progress when they are held back by political red tape. Innovation, by this example, cannot happen when fear, standards of living and morals are set in place. Unit 731 acts as a humbling antithesis for why one should not indulge their curiosity to an extreme, as it could result in a disregard for life, infested by political, racial and religious dogma when left without boundaries for exploration. Given the arrest of dozens of Japanese researchers for war crimes committed in the facility; the punishment is greater when human life is concerned. But given the US response by giving secret immunity to the captured Japanese researchers in exchange for their findings and data of the atrocities; proclaiming that “knowledge is power” is no longer a farfetched idea.

The Manhattan Project of the 1940s, which already understood the dangers of radiation, opted nuclear fallout over diplomacy as a last-ditch effort following Japan’s refusal of surrender and threat of possible nuclear retaliation.

Moving to 2018, consider He Jiangkui’s genetic alterations of twins Lulu and Nana to prevent their development of HIV-1, without the consent and knowledge of the parents or university involved, resulted in a shortened lifespan for the twins and a lengthy imprisonment for the rogue scientist. His trial sparked legitimate fear that, if conducted legally and globally, genetic engineering using CRISPR technology may spiral into eugenics outside of the public eye and without government regulation. I make note of this in a UCL Kinesis Magazine article “Made in Whose Image“.

Is Knowledge Desired | Is Knowledge Required

With Doctor Faustus and Frankenstein dishing the flaws of accrued knowledge as a tempting force to disregard nature, knowledge is in fact, desired. Yet it is it required? That depends on what this knowledge is being applied to.

Right off the bat, I will admit, knowledge is something I am erratically taken with and pursue within reasonable measure. No mad scientist here. But, when I do not have an answer, I am under great stress, especially on existential matters. When the knowledge I gain is unpleasant, I may undergo anxiety, yet I do not have a preference for good news, bad news first. Truth be told, we may believe knowledge is desired among all, and would defend that point, but it is not so simple.

Why would we claim that knowledge is desired, but we do not actively seek it?

Claiming that knowledge is always desired, keyword italicized, is a logical fallacy. No, not all humans desire knowledge, or at least the general consensus is that everyone knows something, but not everyone tries to seek everything. It is a philosophical viewpoint from a single dimension, separated by degrees from social and mental factors. Example: if you asked Person N if they want to know about thing Q, person N will likely say yes out of mild curiosity, unless it concerns or hurts them. This is a defense mechanism. Logic mode: affirming the antecedent. If you offered to tell me the dozens of random ingredients in my favorite foods, I might reject you, and seek peace in my willful ignorance. But knowing the ingredients in what you eat is fair game.

In this example, knowledge is not always desired when the personal effect is challenged, as it reveals a vulnerability. In short: we don’t like when others tell us about ourselves. Denying acquisition of knowledge is the same as pretending we do not have to act on it, and are therefore safe from the effects even if it bites us later.

But what about when knowledge is withheld for legitimate reasons, and can still hurt us?

I am reminded of the Safire Memo, written in 1969 by the Nixon administration that prepared a message detailing the failure of the Apollo 11 mission. Two days before it landed on the Moon. A speech was set in place that would prepare for their demise for unforeseen mechanical issues. Or Apollo 13, coining the famously misquoted “Houston, we have a problem,” where an explosion occurred on board the shuttle en route to the Moon. bad enough that an engine was lost on liftoff, of all times. Among other problems caused by lack of foreknowledge, returning to Earth was chief to resolve. All in all, there are legitimate reasons to withhold knowledge, but we never know who it hurts.

Sometimes we may ask if knowledge is desired from our environment. Surely, from the age of intellectualism in the early 20th century upon the development of literacy, we are encouraged to read, maintain notes, journals, and overall stay curious of the circumstances surrounding us. How our world is formed, by whom and its overall purpose become flyaway topics we gain cursory knowledge on. Yet when we question how much knowledge is considered as “knowing”, we run into gatekeepers who will presume cursory interpretation is done without aim or purpose. I argue instead that knowledge gained does not require application in a real-world scenario, and this includes conversation and work-based requirements. Knowing the formation of the atom bomb does not assume I will know or keep an interest in creating one, and this is a crux in Faustus and Frankenstein: is there knowledge that exists that should be left alone, whether it is accessible or not? Does the impact and implementing of that knowledge, directly or indirectly, make a difference on if we should pursue information?

Often, knowing is not a choice. We cannot actively deny bits of knowledge when our senses absorb information unconsciously. Consider an act of hindsight; when Einstein penned a letter, warning President Roosevelt of the new and possibly atomic weapon, the Manhattan Project was established. In hindsight Einstein mourned the result of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, realizing that inaction would have been preferable if he had known Nazi Germany would have failed to design their weapon. Such is the issue of technology and its visceral connection to transference of knowledge; we cannot assess something before it exists. Walking back a decision comes after we seek out information, which cannot be afforded in wartime.

Knowledge integration is not a choice. All people know something. There is no such thing as a good for nothing. Moral and ethical knowledge with consequences are even less likely to be negated and ignored when lives are concerned. This way, all knowledge is valuable, but first, there is a hierarchy and priority to knowledge, and Faustus and Frankenstein’s pursuit to command natural forces ranks high. And second, once it exists, its apprehension cannot be avoided. Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow, but someday. Instead, we assess it when it is brought to our attention, and its conscious acceptance can be postponed.

We may ask what the point of all of this is, if to know is unavoidable. If there are right and wrong things to know. If we should ever know, and will we know. Why we were born with the capacity to think, to feel, to do, to be. The fun is not knowing. The dread is in not knowing. The point of existence is in not knowing. Or is it?

The pursuit of knowledge, therefore, is not inherently evil or blasphemous. It fits to describe Faustus as flawed by employing his knowledge for his selfish ambition. Victor, similarly to Faustus, holds a moral dilemma rather than a tragic one. As both stories progress, the “should” in the question of ambition is called upon, and is directly tied to one’s happiness and not considering consequences of their behaviors. This is disregarding religious dogma, and investigating the moral character of men in positions to gain knowledge, power and resources.

At the end, even if we should not, someone will.

I will end this with a little quote on conversation:

There is no such thing as a worthless conversation, provided you know what to listen for. And questions are the breath of life for a conversation.

James Nathan Miller

See you soon.

Sincerely,

Nicholas

Works Cited

Marlowe, Christopher. Doctor Faustus. Dover Publications, 1995.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft, 1797-1851. Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus : the 1818 Text. Oxford ; New York :Oxford University Press, 1998.