“In war, not everyone is a soldier.”

Tagline, This War of Mine

In a brutal winter night forecast by the clunky FM radio, I scavenge for the fourth night in a row, feeling less like a ninja and more of a rat trying to hide in dirt. The freezing wind rips through my already tattered brown wool coat, my gloves loosening at the seams. Snipers and looters dot the landscape and prevent anyone from leaving the area. I have little resources, and I approach the small two-story building, sighing after realizing it might be emptied out. I have to check, my friend is at home with a wounded leg and without medical aid, he might die. I use a small crowbar to pop open the back door, and spot a small elderly couple in the living room, staring intently at the radio hoping for the day humanitarian aid is announced. That the war is over.

This war ain’t ever ending. I hope I live through this.

I sneak around the couple to pick apart whatever supplies are left in the basement, and the couple spots me. The older man, hunched and walking with a cane with windswept white hair asks in a scared tone what I am doing. His wife remains seated, unable to do more than shake with wide eyes. They believed they were hidden, with the lights off and sounds muffled, and didn’t realize someone would find their way here under the rubble and snow. I keep searching the boxes. Food, water, medications, blankets, the occasional bottle of booze, anything. The old man pleads with me to leave them in peace, pulling my arm as if to force me off their supplies. I warn him against trying that again. I’m about to throw up knowing I am stealing from people who need it. I feel the tears welling but my hands cannot stop moving. I throw everything I can into my bag and run, but not before he grabs me again.

On reflex, I swing. He collapses. It is too dark inside to see, but my flashlight catches a still frame on the floor. A screech from the wife.

I run. At home I unpack the items: some canned peaches, bandages and dirty water bottles.

Two days later I wonder to myself: are they okay? Should I go back and help them?

Are they even alive?

Ethics and Morality in Video Games

I’ve put off this game analysis off for awhile, since I was at a phase in life where darker stories would affect my mood and leave me either in contemplation or depression. And that is why the game’s darker tones are genius. Eyes moist with tears, I understood later that I was playing in a simulation, only a mere fragment of imagining of what true refugees endured during war, and even this is no comparison. For a casual gamer averse and safe from war, I took the game for granted.

This War of Mine is one that hits both notes, and spectacularly too. It begins its grey-ish dust theme with a Hemingway quote:

In modern war, you will die like a dog for no good reason.

Though Hemingway refers to patriotism and the value of self-sacrifice from a traditionalist standpoint, the game applies this logic to everyone living behind the militarized zones, packed to the brim with bandits, soldiers and ordinary people trying to survive without resources and moving through shell-shocked terrains. Stepping outside often means a death sentence through constant sniper surveillance, and players must manage their characters’ hunger, dehydration, exhaustion, injuries of scaling severity and illnesses.

The game follows a very narrative style of adventure, and this is great for me given that narratives and epistemological lenses are my favorite branch of discussion and research. With that interest, I became emotionally invested in the decisions I make during a playthrough.

Should I have given the last of my medications to the girl who came to the door trying to help her wounded mother? Was I right to trade away the last of my ammo for two cans of food that cannot feed the three people I have to manage? Should I leave my wounded ally asleep in bed alone while I scout the dangerous supermarkets at night? Should I hurt the elderly couple and steal their food? These decisions are made split-second, and each of them pang with a resounding guilt that leaves me wondering what could have been. On returning home, I find my place was ransacked and my sleeping friend was critically injured, but I do not have medications, having given them away to the child who might be nursing her mother. Many of my choices left me wondering if within I am a pacifist or a sociopath, something the developers intended. In This War of Mine, players are not given enough time to think on the result of their decisions when the next life-threatening crisis is at their doorstep, and the somber energy of the gameplay excellently displays the difficulties and whiplash that comes with being an innocent surviving a state of war. Now, I cannot lay claim to these experiences as my own, I do not and have not experienced widespread violence, oppression and suppression, although the developers’ work shows that there is a deep personal and historical experience derived from the 1993 Siege of Sarajevo that shapes the games’ form and direction:

And in Warsaw, actually, there are still many people living who remember how the city looked during and after the Uprising. When the city was completely destroyed, and people were trying to survive despite all the military action around them…

…In Warsaw, actually, there are still many people living who remember how the city looked during and after the Uprising. When the city was completely destroyed, and people were trying to survive despite all the military action around them. …[Another colleague who] was with me at Axe Grind Studios, his grandfather survived the Siege of Leningrad during the Second World War. So she doesn’t like to talk about it much, but he shared some really thrilling memoirs with us.

Pawel Miechowski – 11-Bit Scriptwriter for This War of Mine

There is rich lore research peppered into the game design, starting from eyewitness accounts and ending with literature reviews echoing the Balkan Wars of the 1990’s

There are far too many unknowns and loose ends in the game that reflect real-life pontification of our moral compass, and knowing these decisions have consequences leaves me on guard with everything I do. Whether that be the decision to lockpick that sealed closet or climb through rubble, a player is reminded of the time and granted situational awareness, made easier by the game’s 2D side-scrolling format. The morality as a game mechanic is achieved through ambiguity, ironically. Not knowing if your choice is the right one creates due stress, influencing how you react later. Being on-guard is a result of this stress, and altruism is a luxury one cannot always afford (Pötzsch, 2015). Altruism is considered an important factor in maintaining humane behaviors in calamity (Midlarsky 2011) and yet is costly in-game; giving away resources can kill your beloved, family or friends and unlike games encouraging respawns, once a character dies, the story marches forward without them, uncaring of who makes it to the end. Only one character’s survival is necessary.

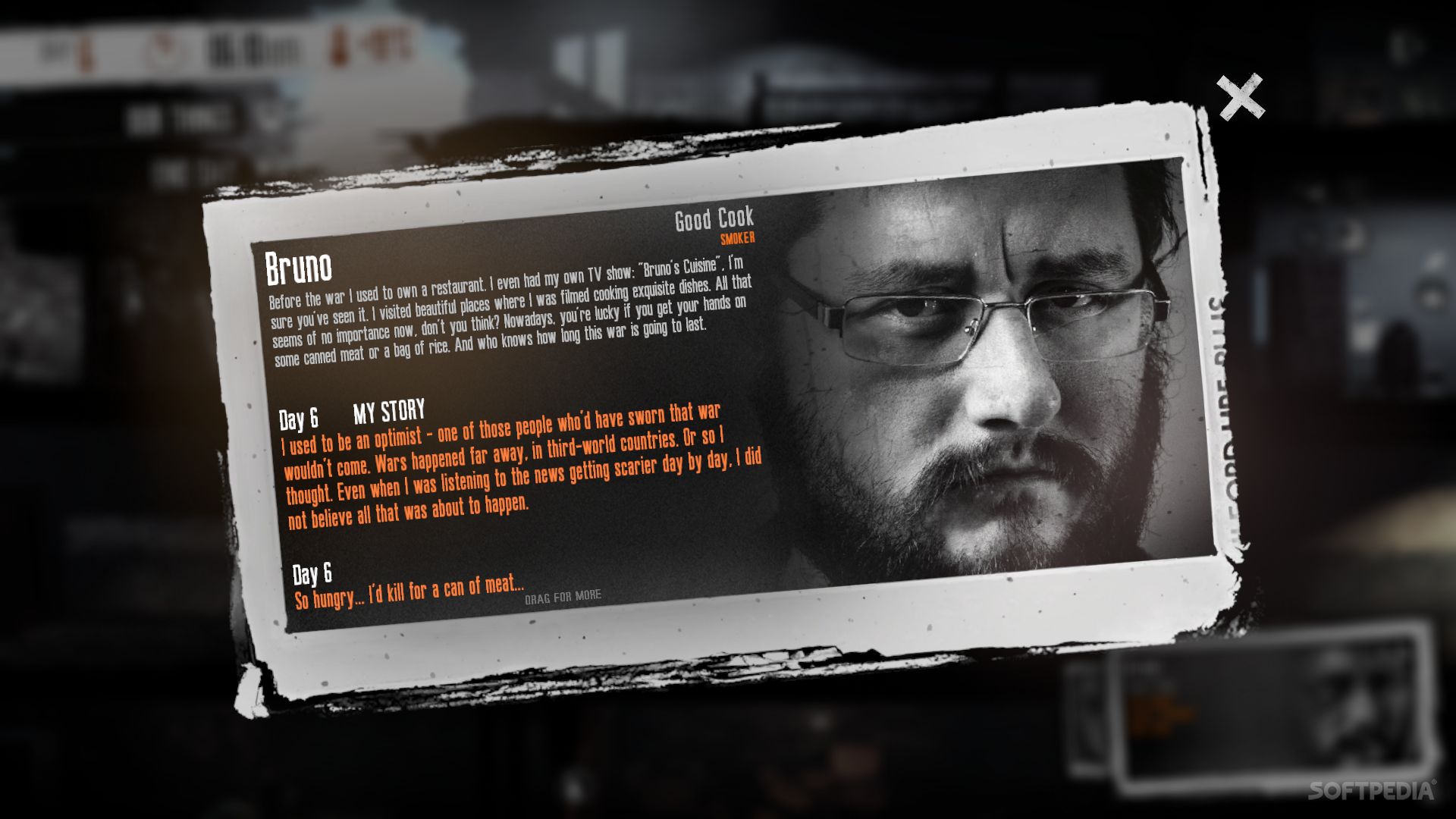

The beauty of playing this game when blind is that there is no learning curve or process to be shown the ropes. Players are given a baptism by fire as the civilians are by surviving without instruction. This is entertaining when each character is dynamic, with backstories and motivations relatable and best, achievable. Chasing the pound of coffee beans, growing that tobacco and wanting to survive the winter are common to want, and the developers do a bang-up job in interlacing humor, realism and humility in messages recorded in the diary by the survivors.

The Moral Craft: Combining Morality and Technology

One goal of This War of Mine is to have players be forced to think quickly, oftentimes apathetically. This mindset changes overtime with the inclusion of moral play, which is not an obvious nor immediate change, instead it is included in the play itself. Sicart (2009) posits that a typical player thinks with a strategy in mind, and this balance is thrown when faced with irrational, real choices. You and I, the player, are faced with impossible situations every few minutes in-game, and players are not evaluated by performance, choices or moral compass. If you choose to give away medication to the less fortunate, your allies may die and the game neither punishes you or allows you to walk back the decision.

We cannot undo reality or the consequences of our actions. There is no morality bar to demonstrate where you stand, it will not determine with certainty the ending you receive. The process is beautifully organic, with players able to make mistakes in a simulated setting to better assess their own priorities. While it would feel awful to let a child walk away hungry, the game reminds you via diary and radio that your life is equally at risk. You can die at any moment without a valid reason. The game forces you to venture into dark and dangerous locations without any certainty you will find resources, placing players in constant fear and reflection of what it means to experience war. It is a grim example, as it offers imperfect choices with no positive outcome.

Day 1 marks the beginning siege and your first priorities are food, first-aid supplies, and tools to help break into houses and build necessities like beds and wood-burning stoves. These requirements do not disappear once you have them; you must maintain them carefully and ensure they are not stolen or overused, teaching players to take inventory and make sacrifices.

But there are also creature comforts and efficiency improvements to be made. A simple work bench can become a fully-equipped carpentry and metalworking shop. A stove can be upgraded and made lavish with fully cooked meals firing off it, assuming you take the time to repair and fortify it. Suddenly you might thrive and be awash with medicines, foods and items to trade with. You won’t need so many resources just to keep your head above water, and you can even start building things like comfy chairs and lanterns so that you can maintain a semblance of civilized life as Katia records her audio and Bruno yearns for coffee. That will help your characters as well, giving them physical and mental refreshment to help them endure their circumstances. Maintaining mental health in the game, as reflected in real life is key where depressed characters underperform and are susceptible to suicide.

By the end of the story, whether you kept your character or party alive until the end or not, you receive a defining message detailing their fates and the progress of the war. It took me a great many tries to make it past the first ten days through the games’ baptism-by-fire design. I loved it. I hated it. I feared it most of all. I could not know what was the right decision to make, and dreaded any moment I saw “the night is coming”, knowing that I made questionable, sane or outright stupid decisions throughout the day. Twelve hours spent digging through rubble would be better spent foraging for food in a bombed out apartment building. Yet, the thought of finding something valuable to trade for a chance to trade for food was too good to pass up. My first runs ignored medications and bandages assuming my characters would hold up through it all. Naively, I did not think of the environmental or structural damages my characters would have to survive and took their health for granted. This is not helped by the fact that I would sacrifice ones’ daily meal so another could eat and search the streets later at night. I eventually wisened up to be considerate to my new virtual friends and use their skills accordingly to their specialties pre-war.

And yet, I could not be a good person.

Good, if we define it here as performing an act of kindness toward another with no ulterior motives, is impossible in the game. While you follow basic heuristics and keep killing to a minimum, you are unable to be good without letting yourself die. In war, monsters are made. The nicest and kindest are forced into erratic, dangerous states of survival. The primal form of us all is born of violence, and repressing this violent nature – per Freud – is part of our social understandings of one another. In war, these are obsolete, morality is questioned, ethics are discarded, and laws are meaningless. Survival for you and your count for the best, and strictly defy the classical philosophical definitions of the “Good”:

Intrinsic Goodness — valued “in itself,” or “by itself,” or “for itself,” and not for the sake of anything else. Friendship and humor are sometimes interpreted to be “intrinsically” good. They are often referred to as “non-moral goods.” While not required, humor is a good in that it enhances your mood and the dispositions of others. In that sense it is “intrinsically good.” It’s good in itself. Goodness is directly correlated to the “moral compass” of others causing them to act good.

Other examples, “moral” and “non-moral,” are:

1) Wisdom and Compassion for others (Siddhartha Gautama, “Buddha,” the “enlightened one“)

2) Acting humanely and honestly for the service of others in “Cosmic Harmony” (Confucius)

3) Living a reflective, “examined life” (Socrates)

4) “goodness,” “truth” and “beauty” (Plato)

5) “happiness,” or “flourishing”: actualizing one’s potential as a rational being (Aristotle)

6) love, compassion; divine presence (Jesus of Nazareth, “Christ,” Matthews 5:29)

7) religious experience; faith, hope and love (Paul the Apostle)

8) a “good will” (Immanuel Kant)

If these can be held as defining “moral” codes then This War of Mine does not have it. “Good” here assumes you are creating some degree of happiness, and the scenarios presented in the game litters hope, not happiness. This is not a critique, but a praise on the realistic outcome of combat and prayers for the violence to end. You play the innocent turned gray, turned cold and traumatized fighting for their survival and I thoroughly enjoyed it.

With the current day Russia-Ukraine war, I wish hope, love and survival for the friends and families around the world enduring the horrors of war. May the sands beneath your feet be warm, the stone be smooth, the air be gentle and warm, may the peace return.

Sincerely,

N