Science fiction has often thrown readers and viewers for a loop in a WHAT IF scenario in parallel universes and alternate realities. It also happens to be one of my favorite topics despite the massive headaches I am left with when considering them, as the existential crisis raised by this rabbithole of questions is… interesting to say the least. I will do my best not to exhaust the page with esoteric phrasing and quibbling exasperations of the topic (much like this sentence!). Speculation and wonder is a healthy act, and a sign of an inquisitive mind; it is necessary to comprehend that which is real and tangible. What then of time? Of the dimensions? Are they not real simply because I have applied restrictive logic to speculation? The third dimension applies to the physical plane, whereas the fourth implies time must be able to move up and down in a malleable way. I digress.

When speculation becomes dialectic, theories become exhaustive in an attempt to define some concept – I say this through a literary analysis lens. Speculation is a traditional aspect of who most of us are: curious, pious and grounded sorts who seek answers. It is designed to grasp the concrete and the real; where it does not exist, it will be created. Speculation can be outlandish, but when rooted in the concrete facets of reality – the five senses – moving from the mortifying plane of “conspiracy” to a map of roads and possibilities to fit a held belief, it is incredibly useful.

Modal Realism and Platonism

For me, understanding metaphysics did not start grounded in Kant’s work, but in Eric Steinhart’s, followed by a dive into David Lewis’ Modal Realism, found in his 1986 On the Plurality of Worlds text. Here, Lewis questions modal logic, or, that which deals in logical statements that use what does not exist. An example: “I could have grown a foot taller”; I was not born to tall parents but did have tall grandparents, but something that statement does is affirm the precedent. There is nothing here that argues I could not have had the potential to grow tall, yet it did not happen. So in what way is it true when the concept is sound, but the reality of it does not exist? It becomes speculation.

Lewis suggests the existence of an infinite number of possible worlds, each with their own affirmations (such as being tall in one world and shorter the next). However, because we do not hold this to be true without sensual affirmation, it rings as an abstract concept. Modal realism makes this abstract possibility a concrete reality, without need to experience them. They exist, and the manner they exist brings a strong connection to the butterfly effect, that one reality moves on where another has ended based on major and minor decisions made, as well as switches possibilities at birth. That said, the worlds are organized on a principle of maximal fecundity; logical statements on modality, per Lewis’ sentiment, rely on the existence of parallel and opposite worlds to hold authoritative weight. These worlds are quantified on maximum fecundity; if the possibility exists and the logical statement is sound, a world must exist that accommodates that reality. This is divorced from our notions of encountering said reality, much like those who believe in a deity they cannot physically see or hear; it is logical to believe reality was created by an omnipotent being, thus a reality exists where this is true. It also allows them semblance of hope and safety in a, quite honestly, vast, unknown and terrifying world.

It is imperative to state that because these other worlds, realms and planes are parallel, they do not, cannot, and should not interact. Thus, the need for speculation. We cannot grasp that which is not physically present to our five senses. Consider Neoplatanism and the question it raises on why matters of the physical world exist. It is unanswerable in its current form, unfortunately to say, and should we discover the reason for the worlds existing the way they do, we may be driven made from the revelations. Perhaps we are not yet ready for that knowledge to become ours. Lines of thought raised by Leslie and Leibniz in Leslie’s Immortality Defended offers a Platonic construction of worldviews and reality. Reality is both a fluid and a fixed structure, broken into abstract and concrete realities. abstract realities consist of intangible, invariably real concepts like mathematical objections; all manners to express the number one (I, 1, uno, one, ichi, etc) are fair in their inconsequential value, because the symbol for “one” and the concept of “one” exist independently of one another. Yet the number one does not float off in some distant universe, we understand it to be right on earth, waiting to be summoned through utterances and physical gestures to quantify something physical. This makes it an abstract concept, dependent only on the conveniences of space and time, without ties to Terra.

Concrete realities, such as ours, can be perceived with knowledge and use of the five senses. Planets, people, food, kittens and rainbows, these all exist in the concrete reality. If concrete reality did not exist, abstract reality still would; concrete structures depend on the abstract to define, describe, qualify or quantify them. The universe still held a number of planets before Earth, long before humans found a way to count and see them.

Leibniz asks critically of abstracted reality: if there are abstract descriptions of other possible worlds, which an indefinite number of possibilities exist, why do we lived in (potentially) the only actualized one and not another? There are implied suggestions that possibilities like this, much like possible worlds and realities, are “quasi-sentient” in actualizing themselves, and strongly push for this actualization based on the degree of perfection they hold. Simply put, the more ideal a world is for inhabitance and flourishment, the greater its drive to exist actively and concretely. Not unlike people seeking purpose in their lives, but on a massive scale. Unseen, intangible worlds become tangible and seen. Leibniz argues later in the work that we live in the best possible world, with the greatest degree of relative perfection in comparison to other abstract worlds (which further implies other peoples and realities live in the bizarre world and consider that concrete). Yet, how do we call this existence a “perfect” actualization when there is an untold amount of suffering on, through and in what we can see? It is possible to claim then that perfection does not equate to peace of mind, rather we must adapt to the suffering and make good use of our time over critiquing the flawed nature of perfection.

Who or What Chooses the World?

In with Leslie’s argument. Why would the infinite corridor of unlimited worlds choose our world to place a reality in and not others? Leslie suggests stacking up the infinite possibilities with the finite actualities. I use infinite in this context due to its non-quantifiable nature, yet our imaginations bind us to a limited number of possibilities. There must be realities incomprehensible to us, designed to drive us to insanity. Leslie calls on Baruch Spinoza’s excellent summary of the universe being the cauldron of a divine mind, though this divine may not be inherently religious, stand for a god, or require worship – Spinoza uses the phrasing lightly to describe a powerful entity and not an omnipotent human-like god. Leslie states that stacking up the infinite possibilities against the finite – the Selector – causes a narrow range of worlds to actualize and birth into reality; what Leslie does not know is how the selection process is done. Understandably so, there is no current way for humans to understand the cosmic workings of decision-making, assuming this is even a conscious decision of the universe itself.

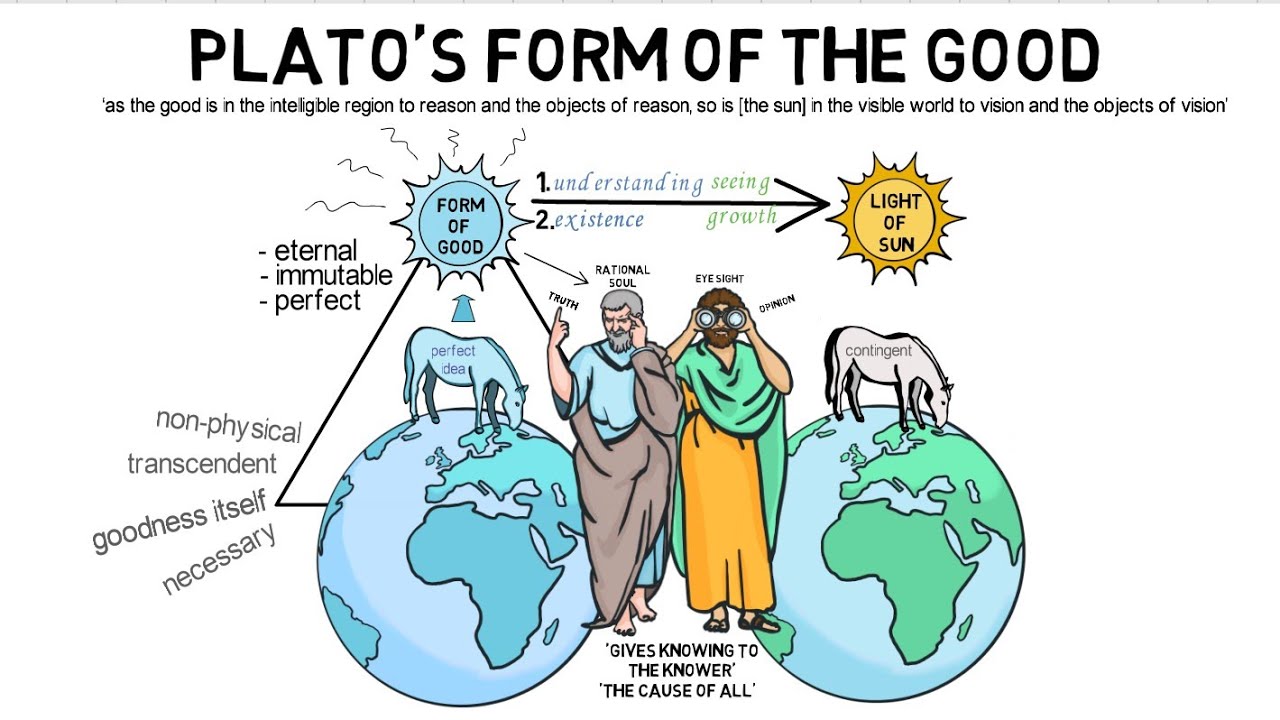

The Selector is not a person, which questions the existence of a consciousness, but a precise and methodical principle which chooses realities on pure calculations. Plato’s view in comparing the Selector is equated to the Good. The Good is neither concrete or abstract but as the decider of our world, because the Good deemed it so. What exists and does not exist is done on behalf of the Selector/Good. This includes our own existences.

Does the Selector/Good choose the best possible scenario? The evidence suggests yes, based on its own unknowable criteria. Who is to say that this is not the worst possibility the Selector has chosen, due to moral and ethical reasoning – human concepts – being absent in decisions of disembodied principles? Leslie takes a shot at it, stating that if we should conclude that there is an objective difference between worlds of suffering and worlds of pleasure, that possible worlds can be arranged in a hierarchy of different value. If a world allows us to thrive under maximal pleasure and minimal suffering, if we could not erase suffering altogether, that world will be placed higher up on the hierarchy due to its closer degree of affection and be actualized faster than world prioritizing suffering and not pleasure. If one world is objectively worse than another based on quality, the worlds then must have both descriptions and values placed on the contents of their universe. Much like how we assess foods, housing and fashion, the Selector determines which circumstances would best fit reality, hence Plato’s argument of the Good. The rankings of the world fall in line with Leslie’s axiology with the Selector only choosing the most perfect world an example of axiarchism. We suffer in increments on a daily basis yet the world could be worse, more dangerous, and less inhabitable by people. It makes sense then to choose the best “possible” world than to risk branding a world as the absolute best or worst of them.

There are issues in being the “best” and “worst” universe: if the best universe is devoid of anything bad (i.e. not this universe) then this universe cannot be the worst due to the implication that the worst universe is devoid of good. This is, of course, based on human reasoning of “good” and “bad”; even in our own species we define these terms quite differently, and natural disasters in the world are bad for us but not necessarily bad for the universe itself. It may very well have a pre-defined definition, if any, on the morality of behaviors and reactions. Steinhart’s theory posits the logically fallacious nature of the “best” in terms of circumstances through Leslie’s axiological lens: instead of selecting this ideal world on antiquated criteria, the Selector/Good chooses the “better possible” world that can sustain itself and evolve itself into a greater ideal universe. Simply put, the potential to grow and perfect is chosen over an already perfect world. Darwinism is in play in Steinharts’ Lewis-like, Leslie-esque foundational views as he believes there exists a multiverse that was born exhibiting a trajectory to become complex and perfect, eliminating the bad overtime without external intervention to choose this outcome, and adapting to the new spatial environment. This is not unlike how we expect our children to one day adapt and learn from the world’s flaws, to better thrive on their own.

“Tiers” of the World: Hierarchical Notions of Pain and Pleasure

Physicist Max Tegmark’s seminal autobiography Our Mathematical Universe: My Quest for the Ultimate Nature of Reality is a tall order. Tegmark begins with a recount of scientific development over the last few thousand years and the breakthroughs that have created modern medicine. In the second half of his work explores the cosmological rankings of the multiverse, in a handy theoretical format.

Level I: This relies on the theory of inflation which is the widely understood phenomenon that the universe is constantly expanding. Should this be an eternal process, then space, matter and particles would have no end, signaling the lack of a fixed boundary in the universe. This means there are and will be an infinite number of observable quarks and stars in the observable world. As this number continues to increase beyond quantifiable means, with the number of ways to arrange them, there will always be a finite amount of worlds at any given nanosecond until expansion. Meaning? At every second there is an infinite expanse of possible universes, planets and existences, with infinite variations, realities, morals and flipsides of our own world. This does assume universes within universes, but with the “possibility” scenarios, all is possible.

Tegmark refers to the “universe” as the bubble we can physically see in our universe. Light speeds and the billions of light years between worlds affects a telescope’s vision of the distance, the farther a telescope is able to view, the farther back in time one can see. Dinosaurs may still be walking a planet in another galaxy within our sight, but by the time we can explore it or the visuals become clear, these dinosaurs would be long extinct. Depending on the amount of light years between worlds, that world existed that many years ago in our universes’ life. Yet, if we so could develop the technology to see past these infinite worlds, we would come across a great expanse of cosmic gas and nothingness, Tegmark claims. None know what is beyond the edges of the universe, though there are theories of there being nothing at all, which is a dangerous existential game to play. We may never know why the universe is here, what began time, if there exists worlds outside time and space, or why we are ultimately alive and able to make these lines of reasoning occur.

Tegmark closes remarks on the Level I multiverse with the claim that if infinite worlds in this ever-expanding universe are true, then there must be at least one planet or plane that has identical and opposite copies of ourselves. Even miniscule bits may be different, with the other universes’ me learning more about botany than history, for example.

Level II: The popular string theory holds up the multiverse, and the irony of that statement is not lost on me. This level theory picks up on an earlier point of parallel experientialism, packed in a neat metaphor: this multiverse has us learn and gain perspectives differently from our counterparts, which includes habits, behaviors, beliefs and taught subjects like history, literature, and physics. The foundations of physics would be the same if we are to account for Tegmark’s argument that mathematical concepts would be the same between worlds, though I argue here that if the worlds are truly opposites, the math behind how we identify things would be askew as well. In physics, the charge of a proton and electron would change, as would the amount of cosmic energy in the world. This theory of the multiverse is a real head-spinner, as it contemplates the existence of a barren world that is not sustainable for any life. Tegmark argues for the existence of these empty galaxies as a possibility of the ever-expanding world. This presumes the universe has no limit to its expansion.

Level III: The Many-Worlds Interpretation. Hugh Everett III’s erudite theory on the existence of many overlapping, identical and opposite worlds is derived from his work on theoretical quantum mechanics. His work concludes, opposite Lewis’ theory, that many of these worlds are not parallel, but perpendicular and are designed to interact with one another. Theoretically speaking. Everett later posits the Hillbert space, where worlds exist parallel but at some point evolve and branch off from one another if possibilities overlap, and cause the actualization of each possibility.

In simpler terms, parallel worlds with similar foundations and factors of existence will touch and cause evolution of both worlds, creating new possibilities.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/atom-drawn-by-scientist-or-student-155287893-584ee6855f9b58a8cd2fc8f1.jpg)

Everett and Lewis stand at opposing viewpoints. Everett’s theory presumes that discovering the infinite worlds is a direct consequence of empirical findings in quantum physics, an accident. Quantum physics understands that subatomic particles cannot behave and interact in the way solid objects (people, kittens, planets) can in the way we do; instead of existing in one place, the subatomic particles are superimposed in every position and angle they can manage. Meaning, they can exist in any place in history, which includes any point in time and space. How a subatomic particle like an electron becomes a fixed object like a person. Everett refutes the idea of a superimposition by claiming there is no collapse in the particle leading to a construction of a person. Instead, all possibilities are arranged on the pretense of a probability, and we are but one arrangement of probabilities that became a possibility, and became “real” through – possibly conscious – decision-making. Among others, we are one possibility that could occur among the millions of different parallel worlds.

Tegmark takes a step back to rein in theories confounded in reality; the models of the possible multiverses are not the positive productions of theories, but are the consequences of theories riding themselves out. Aside from the models themselves taking charge, they are are dependent on fundamentals of cosmology, astronomy, and physics. The eternal expansion and inflation are examples of this, and interpreting quantum physics suggests the possibility of multiverse models.

Rising from the Rabbit Hole

Topics in existential anomalies will always get a rise from me. This is because I am reminded of our potential and bounds of exploration, which are contingent on what we can imagine in reality. Empiricism, or the study and analysis of tangible data ends, and speculation begins. Both concepts are creations of our mind, and brought into reality through our actions or the universes’ intervention. Tegmark’s work reminds me that the most impressive fonts of knowledge and technology in the world began with strange ideas and contemplating the unknown. Are there truly different versions of myself? How different are they and their world from myself and mine? Do the parallel worlds behave in a butterfly effect, where any action I do or not take here affects that world? I fear we may never know. Going far into the unknown left me chin-deep in metaphysics and the constant buzz of questions eventually left me in a constant state of stress. Now I realize that no matter how far I go, I will prove little, see nothing beyond my senses, and would only have a vantage point that teases, not defines. Once upon a time I would relentlessly seek an answer, but at 24 I’m okay with that now.

That feeling may be fleeting as well. Tegmark posits that our habit as human beings is to assume not only that we sit at the center of everything, but are aware of how vast reality is. By grounding ourselves in the center of that reality, we can maintain a semblance of sanity and not feel insignificant to the point of non existence. We know we exist on a planet, that planet is part of a galaxy, then a universe. Draw in Copernicus, for we are the nexus of our world, the sun in our system, and that one special space in spacetime. Many stars because many galaxies, which end up speeding away from each other (sometimes faster than light, since space itself can move faster than light even if matter can’t move through space at such a velocity), and eventually perhaps many galaxies in a single universe will become just one universe in a vast expanse of several others like and unlike our own to varying degrees. And who can say if the pattern goes on further, like Tegmark hypothesizes?

On Speculation

Consider this scenario: you are a cosmological cartographer on some far-flung future expedition to map a bizarre world. Satellite can only get you so far, and you must explore this world, its every nook and cranny. Every rock, flora and fauna is subject to a watchful, interpretive eye. You will need to plan this out, and any old plan just won’t do; after all, what’s more probable to occur, vicious man-eating beasts or sharp rocks? You cannot plan for every possibility, only the most probably to occur, and satellite helps you with that. Plan from there, speculate and envision what might await you, and prepare for that journey,

That is the mark of speculation. Good speculation that applies here. The multiverse concept is not new, we have heard of it in every form of media on the planet already. It has existed through the rise and fall of civilizations and endured religious, political, and philosophical sacrilege. Lewis’ school of thought invariably belongs to an ostentatious and esoteric body of knowledge in suggesting modal realism; this school of thought could see an alien planet, know it existed there, observe the distance, and if other worlds revolve around it. Yet Everett’s contemporary school of thought has us visiting these worlds for photos through a next-generation technological wonder. The world will produce an even newer school of thought that lets us walk these forsaken worlds. For now, we have only plans and speculation to base our developments on, and the curiosity of the world is the most exciting part of living it. We don’t know what fates will await us.

It helps to highlight this: if Tegmark insists that our innermost minds are shaped through Darwinian need to adapt, survive and reproduce, it is no wonder that our beliefs change and our actions are altered to match an individual’s needs. We were designed to detect carnivorous predators, to find food sources, and continue our bloodlines. The universe does not think on this scale, if it is conscious at all. It acts and behaves far diverged from the Fertile Crescent our ancient forefathers derived to navigate the world. It should not shock us what science develops next, including accurate models of the known universe that are counterintuitive to development, which defy our instincts and expectations. We must pay attention to the breadth and scope of our world.

The multiverse is infinite, relatively speaking to us, if we account Lewis’ endless worlds theory, rather than a Darwinian selection of them ala Selector. Schools of philosophy would do well to catch up to the groundbreaking studies of the universe, and science must remain on the path of absolute precision. Leslie and Steinhart should, ideally, manage to adapt and modernize foregone ideas, and anticipate new modalities of speech and existence in a meaningful way befitting our timelines. Our little pockets of reality simply cannot cope with knowing how much bigger and busier life is than ours, but being aware of it helps.

There is also the factor of discussing a topic. Any topic. Leslie’s points are dated, but reading his work’s made me better understand the differences between an abstract and a concrete reality, and the existence of a powerful Selector to decide our actualization. Steinhart argues for the multiverse on a trajectory, and not a static “all world” concept, rather that they will evolve and develop as time flows forward. Speculation is a game of intellectualism, and the top-down implications for philosophy, psychology, sciences and physics is a game of tracing possibilities, learning their probabilities of existence with terrifying accuracy, and allowing lesser possibilities to dissipate in the public and private sphere so greater possibilities have reason to exist.

That is the Darwinian way, in a sense. Another multiverse, one familiar to us.

Til next time.

-N